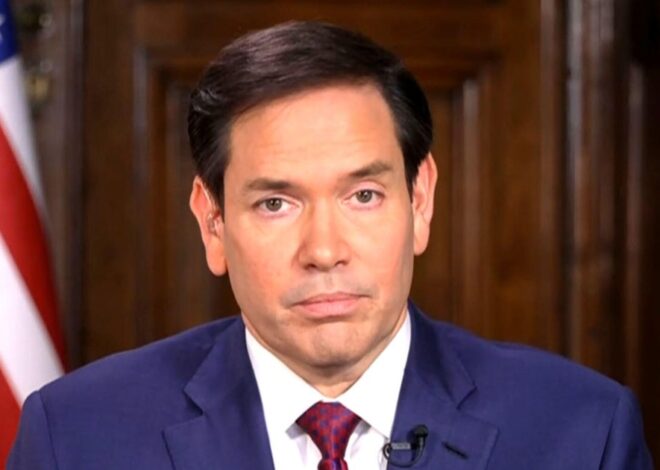

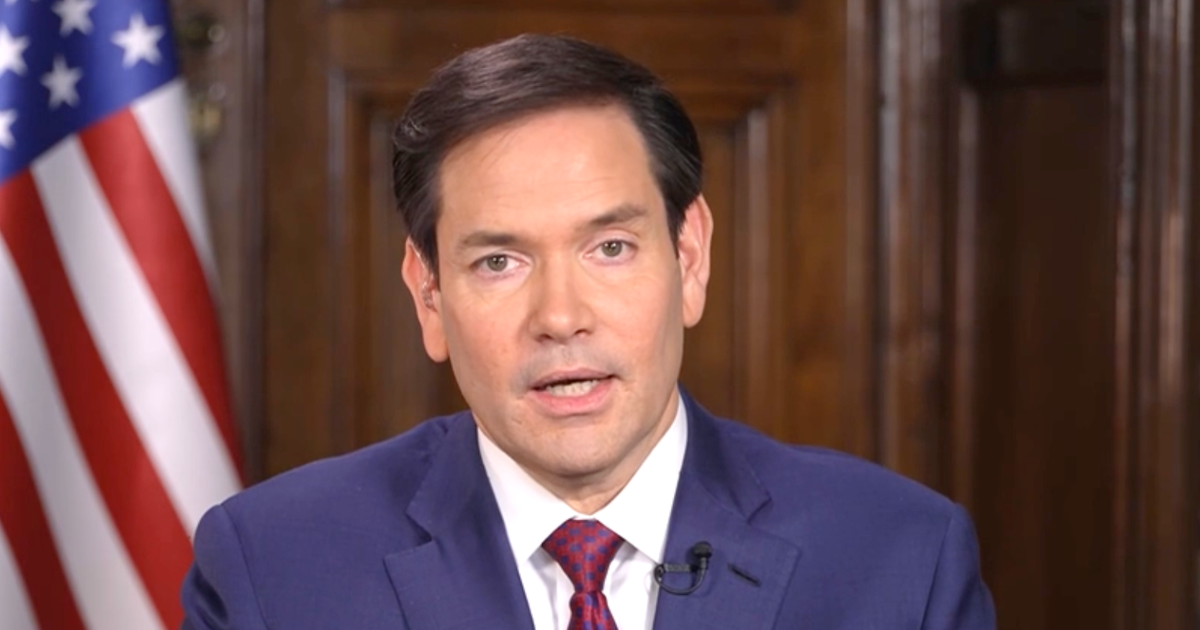

Rubio Disputes Intelligence Community’s Evaluation of Tren de Aragua: “They’re Mistaken”

The Controversy Around Tren de Aragua and Venezuela

In the world of international politics and security, the lines between allies and enemies sometimes blur in unexpected ways. Recently, the spotlight turned towards Venezuela, where a debate is heating up about the alleged connections between the Venezuelan government and a notorious gang, Tren de Aragua. Marco Rubio, the Secretary of State, has been vocal, challenging the prevailing assessments made by the intelligence community. He’s quite convinced that the gang is, indeed, a proxy force for Nicolás Maduro’s government, despite others suggesting otherwise.

Rubio was clear during an interview on “Face the Nation with Margaret Brennan,” bluntly stating, “They’re wrong.” This bold disagreement follows a report from the National Intelligence Council which claims the Venezuelan regime isn’t directly controlling Tren de Aragua. The report, made public through the Freedom of Information Act, challenges the justification the Trump administration has used for deporting suspected gang members under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798.

The Alien Enemies Act is a historical relic, one of those legislative pieces that seems like it belongs in an old history textbook. Yet, the Trump administration revived it, viewing suspected gang members like wartime foes. The move had its controversies, especially since a significant number of those deported reportedly had no criminal past. Imagine, a broad sweep that sends hundreds to a prison in El Salvador, many of whom had no direct ties to crimes.

This tension extends to the federal courts. The administration’s actions prompted a legal tug-of-war, especially after the Supreme Court stepped in, deciding to maintain a block on further deportations of Venezuelan men detained in northern Texas. The courts seem to echo a sentiment of caution, preventing hasty decisions while the legality of using the wartime act in this context is questioned.

Rubio, meanwhile, isn’t swayed. He finds himself aligning with an FBI assessment, diverging from other intelligence evaluations. He believes Tren de Aragua isn’t just a gang operating with tacit approval from Venezuela but a tool wielded with intent. There are claims floating around-maybe not entirely concrete-that the gang has even been used in assassination plots abroad. Rubio mentioned a situation involving a potential contract to target an opposition member in Chile. It’s almost like a thriller novel, isn’t it?

There’s a narrative here, one that’s unfolding with each statement from Rubio and each report released. The assertion is that members of Tren de Aragua, when sent back to Venezuela, receive a hero’s welcome, suggesting more than just passive acknowledgment from the government. There’s a stark image-gang members stepping off planes, maybe greeted with cheers, as though they’ve returned victorious from some battlefront.

Rubio’s remarks highlight a deeper concern, a belief that Venezuela uses this group not just for internal suppression but to destabilize other nations. For him, this isn’t just about one gang. It’s about a strategy, a projection of power beyond borders, with Tren de Aragua as a tool. Whether this view will shift international policy or merely add another chapter to the complex saga of Venezuelan politics remains to be seen. But one thing’s certain: it’s a story worth following, full of intrigue and implications on a global scale.